by Margarita Mooney Clayton on March 22, 2020

After an emotional weekend where my large Cuban-American family gathered in Miami to bury my cousin, Patrick Hidalgo, who died suddenly at the age of 41 the first week of March 2020, I woke up March 9 to an email from Princeton saying that, due to COVID-19, all classes had been moved online for the rest of the semester.

Thoughts raced through my head like: Life is short; God’s ways are mysterious; this is unprecedented. Then came questions: How shall I be? What shall I do?

Benedictine monasticism has been one important influence on my philosophy of education, my spirituality, and my everyday attention to small aesthetic details. But the overnight monasticism of our current situation is challenging for so many—myself included—who crave human interaction to feed our minds and souls.

Leaving Miami meant leaving the giant Suarez clan that feels like a cocoon that fed so much love into me as I was growing up. Returning to a near empty campus and empty streets in Princeton felt even more bleak given that I had so recently been surrounded by so much love in the midst of grief. But education is my vocation: I can’t run from the emptiness I’ve been left with.

Reality hit me hard when I saw in mid-March what normally happens in mid-May: students loading up cars with all their belongings, saying goodbye to their friends; graduating students are not coming back to campus as students ever again. I set out personally to say goodbye to students graduating in May who I’ve known for several years and may not see again in person. As important as Zoom and Facetime have been in recent weeks, those personal goodbyes felt more human—a flesh and blood interaction.

But I firmly believe life’s most challenging times are also life’s most creative times. Being in Miami recently reminded me not only of how far my family has come, but how much we have overcome. My mother lived through the Cuban Revolution and the pain of exile. With poor English and no money, at the age of 21, she arrived to the United States in 1961 with her 13 siblings and parents. She got a job, any job, many small jobs, and scraped pennies together to help her family, little by little pursuing her dream of graduating from college. My mother has an incredible ability to always see the glass half full and to never begrudge her many sacrifices. She told me repeatedly that America was the land of opportunity and that I had the world at my feet.

My mom’s brother, my uncle Xavier Suarez, was only 11 when they came to the United States. Sitting in his apartment on Brickell Avenue in Miami, looking at pictures of him from his more than 40 years in public life—holding elected offices such as the Mayor of Miami and County Commissioner of Miami-Dade County—one might not know how much he struggled when the Suarezes first came to the US. Xavier told me during my recent visit to Miami that he knew things were going to be hard when he went to Mass in English and couldn’t understand a word. But he understood what it meant when his older sister put a single penny in the collection basket.

They were desperately poor in exile, but the Suarezes had their faith, they had their curious minds, and they had each other. They had the Catholic Church’s many spiritual, social and educational services, and they had the friendship of the young Franciscan friar I know as Father Sean—now Cardinal O’Malley of Boston.

Xavier became a scholarship student at St. Anselm’s Benedictine Abbey and School in Washington, DC. He learned to read, write and speak English, alongside his liberal arts education through which he studied science, world history, and literature. My grandfather, Manuel Suarez, led discussions of papal encyclicals over dinner to Xavier’s friends, just as he had with his own students when he was Dean of Engineering at Villanova University in Havana. Xavier went on to study mechanical engineering at Villanova University near Philadelphia, and then law and government at Harvard. He still reads voraciously—especially biography, history, and science—all the while working as a lawyer, holding public office, and writing his own books. When our family tragedy struck, however, his priorities were clear: to support and love our large and diverse family in our crisis, including hosting me in his home for a week.

Before returning to the ghost town of Princeton, I chatted with Xavier about the importance of liberal arts education, and the importance of friendship, community, family and faith to persevere in hardship. We read sections of his latest book manuscript called Fire, Flint and Faith, which is nothing less than an ambitious attempt at grasping the very essence of what it means to be human.

Back in Princeton, I struggled to find ways to connect to my students. I invited all the alumni of the Scala summer programs from 2017-2019 to join a Zoom call. From every region of the US, from a variety of disciplines of study, faces kept popping up online, faces looking for guidance and companionship during unprecedented times. For people whose vocation is the life of the mind, the closing of nearly all educational institutions is jolting, to say the least.

We agreed to meet weekly through Zoom for fellowship and study in order to ponder questions like: How do we care for those who are suffering economically, physically or spiritually right now? How do we keep feeding our minds and hearts?

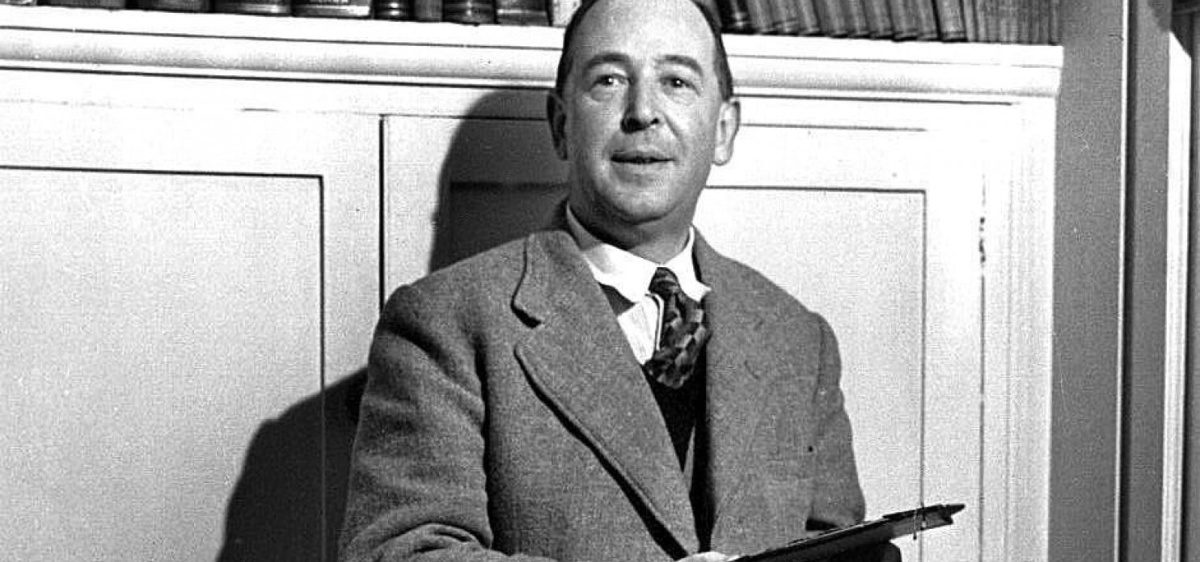

I immediately sent out to all the Scala alumni C.S. Lewis’s Essay “Learning in Wartime,” where he reflects on the life of the mind at Oxford during wartime in England. In no time I received this heartfelt reply from Henry Burt. With no regular schedule, and no regular expectations for how to be or what to do, I just threw my heart out as a teacher. What I got back from Henry shows why I love teaching, and that it is possible to teach—even virtually—in these unprecedented times. A heart and mind at work is a beautiful thing to observe—God has given each of us a conscience, and the greatest thing I can do as a teacher is stimulate a student’s inner core with great books, great authors and big questions and then let God do the rest.

I hope Henry’s dialogue with C.S. Lewis inspires you to faith, hope and love as much as it inspired me.

LEWIS: “We are mistaken when we compare war

with “normal life.” Life has never been normal. Even those periods which we

think most tranquil, like the nineteenth century, turn out, on closer

inspection, to be full of crises, alarms, difficulties, emergencies.”

“There is therefore this analogy between the claims of our religion and the claims of the war: neither of them, for most of us, will simply cancel or remove from the slate the merely human life which we were leading before we entered them. But they will operate in this way for different reasons. The war will fail to absorb our whole attention because it is a finite object, and therefore intrinsically unfitted to support the whole attention of a human soul.”

“We can therefore pursue knowledge as such, and beauty, as such, in the sure confidence that by so doing we are either advancing to the vision of God ourselves or indirectly helping others to do so.”

“As the author of the Theologia Germanica says, we may come to love knowledge our knowing-more than the thing known: to delight not in the exercise of our talents but in the fact that they are ours or even in the reputation they bring us. Every success , . in the scholar’s life increases this danger. If it becomes Irresistible, he must give up his scholarly work. The time for plucking out the right eye has arrived.”

HENRY: Perhaps times of uncertainty humble us because we find frustration in not knowing what we want to know; perhaps a shift to appreciate things (i.e. God’s creation) for their own sake, not for if and how they serve us and our interests

“…do not let your nerves and emotions lead you into thinking your predicament more abnormal than it really is.”

“The second enemy is frustration-the feeling that we shall not have time to finish. If I say to you that no one has time to finish, that the longest human life leaves a man, in any branch of learning, a beginner, I shall seem to you to be saying something quite academic and theoretical. You would be Surprised if you knew how soon one begins to feel the shortness of the tether: of how many things, even in middle life, we have to say “No time for that”, “Too late now”, and “Not for me”. But Nature herself forbids you to share that experience. A more Christian attitude, which can be attained at any age, is that of leaving futurity in God’s hands. We may as well, for God will certainly retain it whether we leave it to Him or not. Never, in peace or war, commit your virtue or your happiness to the future. Happy work is best done by the man who takes his long-term plans somewhat lightly and works from moment to moment “as to the Lord”. It is only our daily bread that we are encouraged to ask for. The present is the only time in which any duty can be done or any grace received.”

HENRY: I have realized this to be a lifelong challenge for me: to live in the liminality of cherishing the present, but still with part of my mind on those “loose ends” that may or may never be tied. I would be happy to discuss coping mechanisms for the short and long term for those who also deal with this anxiety and tension.

“But if we thought that for some souls, and at some times, the life of learning, humbly offered to God, was, in its own small way, one of the appointed approaches to the Divine reality and the Divine beauty which we hope to enjoy hereafter, we can think so still.”

HENRY: I think to 1 Cor. 13:12

For now we see only a reflection as in a mirror; then we shall see face to face. Now I know in part; then I shall know fully, even as I am fully known.

Nonetheless, let us pursue evermore clarity in this earthly life, to know, love, and enjoy God in preparation for all the more knowledge, love, and enjoyment in His kingdom come.